The 'grief window' and other myths...

or... why are we so obsessed with our past selves?

I’m 18-years-old in this picture. Maybe 19. ‘The Bairn’ is scrawled across that teal t-shirt I’m wearing, a leaving gift from the theatre I ushered in. It was my nickname as I was the youngest of the group but, at that time, I didn’t feel young. I didn’t feel old either. I guess I felt free. And happy. Oh-so-happy.

I’m in a techno club in Prague and I’ve just kissed a Czech boy. I remember what he looks like only because I have a picture of him taped in my diary - shorn black hair, wide blue eyes. He spoke no English and we communicated only through our hands… and mouths.

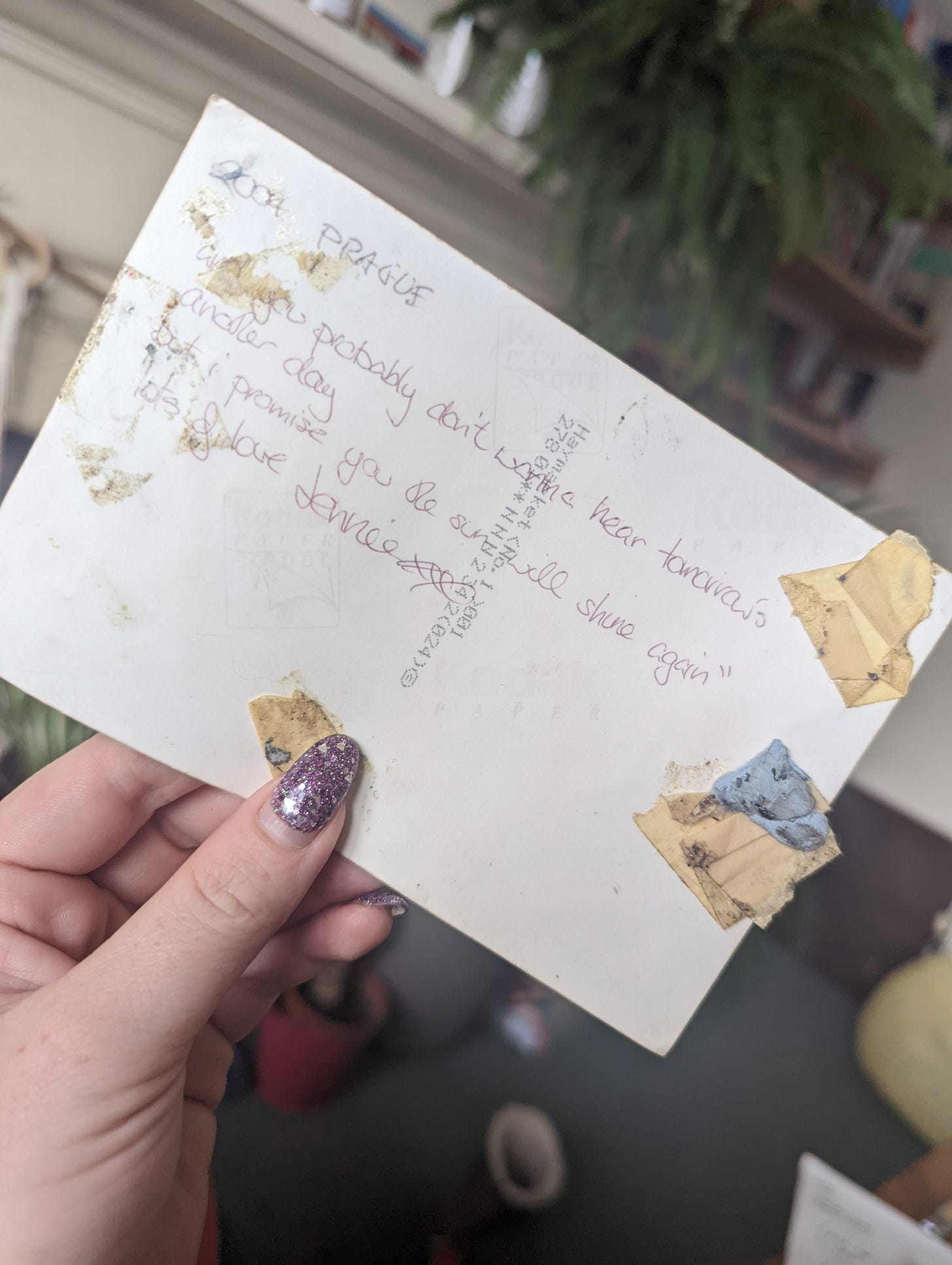

Flip the photograph over and written, in the boxy handwriting of the girl I was travelling with (who I am still incredible close to now) are these lyrics: ‘I know you don’t want to hear tomorrow is another day, but I promise you you’ll see the sun again.’

When she gifted me that picture the thought that I’d ever smile like that, feel like that, ever again, well… that was inconceivable. Any smiling I did was the kind where I’d twist my face into the shape of one, my brain and body numb behind it.

She was gifting me hope.

As shortly after that night, that boy, my mum was diagnosed with a brain tumour. One that we were told would kill her within days, one that came without warning. One morning I was at work, returned as ‘The Bairn’ in that theatre, wondering if a boy (another one) might like me back, and the next I was in a taxi, on the way to the hospital wondering why my dad had said I had to ‘come now.’

Everything changed. My mum lived for months, but they were frantic ones, where one sentence played on a constant loop in my head: “she’s going to die when I’m doing this shot, she’s going to die while I stand in this shop, she’s going to die and I’m not going to be there.” She did, eventually. I wasn’t there.

I wanted nothing more than to transport myself back to who I was in Prague, be the sort of person who could grin so hard it breaks their face. I thought it was possible too. I propped the photo up in the series of bedrooms I lived in after mum’s death (one which was actually a cupboard… that’s a story for another time). I knew I couldn’t bring her back, I wasn’t in that sort of denial, but I did strongly believe that, over time, I could bring myself back.

I’m 37-years-old now and I can see that was as impossible as raising my mum from the ground (or, more accurately, gathering up her ashes and gluing her whole again.) Would I go back and tell the younger version of myself to stop seeking a happiness she was never going to achieve? No. Because I was seeking happiness. I’d only want to tell her to surrender herself to grief. To stop trying to will the grieving process to be ‘over.’ I wanted to go back to ‘normal’ and I hated myself for not achieving that. But the girl above was gone. My grief will never be over.

I felt ashamed of this for a really long time. When I decided that I wanted to launch this newsletter, that I wanted to centre it on grief and, as part of that, I’d be writing about mum, there was this small voice that said “people will think you’re pathetic for still going on about that”.

But I think it’s important to acknowledge that grief will shape your life. That, if it is a ‘five step’ process, then those steps will stretch over your lifespan. They are not milestones that you tick and then suddenly feel better again. I used to say “I wish I cried more when I was ‘allowed’”. I felt I’d wasted her funeral, and the weeks following her death, by plastering on a smile, by going back to work and by spending more time fretting over boys (you sense a theme here…) than by thinking of her. I was angry and ashamed of my behaviour, terrified it could look as if I didn’t love her. “How ungrateful I am,” I’d think. “To not even give her the mourning she deserved.”

I now see I was doing what I could to survive. My body took over and went into auto-pilot. That there is no right, or wrong, way to grieve. If I had spent months clad in black, sobbing in dark rooms, clutching a photo of her (my idea back then of what ‘correct’ grieving looked like) I don’t think I’d feel any different today. There’s no form of behaviour that would make me miss her less.

I think this is true for most of life’s painful experiences. After something bad happens to us we can be left reeling, feeling as though something inside of us has altered but that if we just follow certain steps we’ll feel ‘back to our old selves’ in no time. But why are we so obsessed with who we once were? Life changes us every day.

I like who I am now. I’m not the girl above but I am a different version of her. I’ve experienced pain so intense it’s felt as though chunks of my flesh have been gouged out, that I’ve been walking around with a huge part of myself missing. But I’ve also grown around those wounds. And I’ve learned to smile - a very real one - alongside them.

What do you think? Is there a ‘right’ way to grieve? What would you tell your old self? I feel I’ve touched on a lot in this but not gone too deep, is there anything you’d like me to write about next? Let me know in the comments!

And if you’ve enjoyed this, please share with someone you think it could help.

Catriona, this is a beautiful - and true - piece of writing. My Dad died of cancer when I was 19, after five years of living with the disease; it was a painful watch as his tide receded further from shore. He was only 53; I’m now 54 and that’s a head-spinner in its own right, to have reached an age that a parent never attained but to still feel like a child…

How I describe the loss of my Dad is this (which requires a wee bit of visualising gymnastics, but I’m sure you’ll get the picture!):

Our family - Mum, me and my sister and brother - are on a motorbike, with my Dad in the sidecar. We’re on a wide, open road and can see the path straight ahead of us. But we come to a crossroads, and out of a side street comes that juggernaut called “Death”, and sideswipes us all. The sidecar is sheared off and Dad disappears out of sight, down another road. The rest of us, battered and bruised, remain on the motorbike - but now our direction has been forcibly changed too and for the rest of the journey, we’re very aware that this road has a different view, a different perspective than the road we thought we’d all be travelling on together.

And while we can no longer see Dad, or the scene of the collision, in our rear-view mirror, we remain aware of its impact and how we came to be on this road.

Does that all make sense?

And Raymond, I *loved* your description of grief and loss and hardship being like dark threads in the fabric of our life - they offer a contrast against which the brightest threads are all the more vivid, and we can better appreciate them. Thank you for that leitmotif 🙂

This is such a beautiful honest and brave piece of writing. l love and admire you so much for it.

It is taking me on a journey to difficult places where I need to go.

What especially hit me hard about this piece was the memory of how much i wanted to shield you and your sister from this pain.

And could not....