INTERVIEW: Quarter-life grief with Rachel Wilson of The Grief Network

Losing Young explores the unique struggle of facing grief in your twenties...

I was at a BBQ when I realised it. This thing that, perhaps to others, is spectacularly obvious. It’s an enlightenment that also comes with a side of ‘doh, how could you not have known that.’ But, I didn’t realise it, until that very moment - under Cornwall’s wealthy blue skies. The thing is… I was really young when my mum died.

My second cousin was sitting on the grass, nestled in between her mum’s legs. Absentmindedly, her mum was picking up and playing with strands of her hair. We were chatting about how my second cousin was about to head off for university, about how she was turning 19-years-old. The others, scattered around me on picnic blankets, won’t have noticed: to them this was just standard catching up chat. But I felt as if I’d been thrown across the grass, suddenly hit by the gust of my own suppressed reality. I wanted to ask, “are you sure?” But I didn’t. I smiled, as my head scrambled with calculations, with memories, as I tried to picture myself as I would have been back then.

But all I could see was her. How little she was. It was inconceivable to me, that this girl, innocent and happy and safe at her mum’s feet, could be the same age I was when I lost my mum. I found myself being almost transported into her life, imagining how she would cope if she lost her mum. She couldn’t cope, I thought, how awful to even imagine.

But that had been my reality. It took me 36-years and a casual conversation to figure it out. 19 is not a normal age to lose your mum. 19 is really, really young. So… why did it take me so long to see this fact, that’s as crystal clear as the skies were that day? This was something I spoke to Rachel Wilson about in a recent Zoom call. Rachel was 26 when her mum died and wanted to seek support from others like her, not just those who had lost someone but those who had lost someone in this flux-quarter period of their lives. So she set up The Grief Network, bringing together other young grievers both online and for in-person meet-ups, after she discovered there’s very little specific support for this sort of grief. It’s what she’s labelled as ‘quarter life’ grief and while she goes into this in greater detail in the book, she defines it as:

‘a grief precipitated by the death of a significant person which cataclysmically disrupts your assumptive world… this disruption happens at a time in your life when your world is already unstable, your identity is in flux… for other people your age that instability is a flexibility that can be enjoyed, explored and exploited. For you it becomes a source of anxiety, anger or fear. Grief therefore becomes part of your formative experience. It shapes your identity, your decisions, your adulthood.’

Reading that paragraph (and the book) I felt, for lack of a less cliched word, seen.

For so long I tried to tell myself and others that what had happened to me was no big deal, I’d say things like “it’s worse for my dad, my grandma… imagine losing your wife? Your daughter?” to distract and (I hoped) detract from my own pain. It’s true, what my dad and my grandma went through was awful. But it wasn’t worse. Also, while I was definitely trying to look-over-there my grief away, I was also parroting what I’d been shown of loss. I’d seen and read about parents losing children, about husbands losing wives. I was trying to mould myself into someone else’s storyline, the narrative that I knew. I couldn’t see myself anywhere. Now I can recognise that there has always been something unique about the ages that my sister and I lost our mum (I was 19, Bex will have been 24, 25).

We had to face loss at a time when we were on the cusp of adulthood: a time of experimentation, learning, expansion… There’s so much out there about the turmoil of your twenties: these defining, flaky, flailing and uneven years where, each week, you try on something (or someone) new for size. You’re finding what fits. You’re crafting who you will become. We had to do all of that, grasp at the same life lessons as our peers, while, at the same time, our roots were being pulled from beneath us.

It’s something I couldn’t quite grasp until reading Rachel’s book Losing Young - How To Grieve When Your Life Is Just Beginning. There was so much I wanted to speak to her about, conscious that I’d use the interview time as an unofficial therapy session instead of being professional. Our conversation, and her book, has really helped me to see parts of my past in a more sympathetic way, as well as the things I’m currently picking my way through. I can still feel my own sharp, internal judgement when I struggle with things today, it says stop making excuses, not everything leads back to losing your mum, but recognising the topsy-turvy reality of the time I lost her, how much it will have shaped everything, helps quieten that voice down.

I’d also like to, quickly add, before getting to our conversation that by highlighting quarter-life grief Rachel is not, nor am I, trying to say what we went through is ‘worse’ than any other grief, just that it comes with different challenges. Her book also delves into how, as a society, we’re ‘grief illiterate’ and why that could be, and she interviews a wide range of people for their experiences to portray the differing emotions within grief as best she possibly can (because nothing could fully capture all of grief’s complexity, no matter the word count). It’s a useful resource that could help anyone who has faced bereavement, or is looking to support someone going through it.

You can pre-order it here and here’s part one of our conversation…

As someone who writes about and researches grief a lot, I’m so aware of how the process can be healing but also bring up a lot. I wondered how writing the book impacted your own grief process?

I had so much going on when I was writing it, as I’m changing careers to become a barrister. I've literally spent the last few years studying law and that's all very, very intense. And so having to write this book, whilst doing that was not the most fun time in my life. It was difficult because it was sometimes trying to access emotions that I wasn't feeling because I was just so stressed out with other stuff. I think, also, to an extent wanting to be a barrister and wanting to get myself on solid ground was kind of a response to some of the grief: so much of my life had been dominated by it, then the pandemic and lockdown happened and I was about to turn thirty and needed to figure out what my life would look like next.

I think the most obvious point for me where [writing the book] affected things was when I was coming to write the epilogue of the book. I’ve written for publications before and felt the pressure where they’ve wanted me to add some sort of hope, or for the piece to end on something happy. But [with the book] I didn’t want to do that, as grief just doesn't really work like that. And so the epilogue of my book explicitly references it and says “people expect a book like this to end on a hopeful note. But I'm just not going to do that.” Because at the time I was writing the epilogue, it was coming up to the fifth anniversary of my mum's death and I was like, “this is not a time where I felt very hopeful about my grief. I feel like this is actually getting in many ways harder as the years go by.” I also know that [finishing the book] is not the end of my grief and it's not the end of anyone’s, as after you finish reading this book, it all still keeps going, it goes on.

I’m trying to give people something that’s accessible to read, and hoping that people who aren't bereaved are reading it just as much as people who are. [I’m] being vulnerable and exposing my own grief and how I feel about how that really developed over time and being truthful about the fact that you know, it's probably gotten a bit more negative. I'm sure I'll go through phases and feel fine again, but I had to stay quite true to how bleak it can be.

I had highlighted a bit at the beginning that says people want a beginning and a middle and an end. But that's not how that's not how grief works. I’m the same, I always find it so hard to end anything that I write as I feel like I’m just trailing off and being like… I can’t really give you an answer, I don’t know!

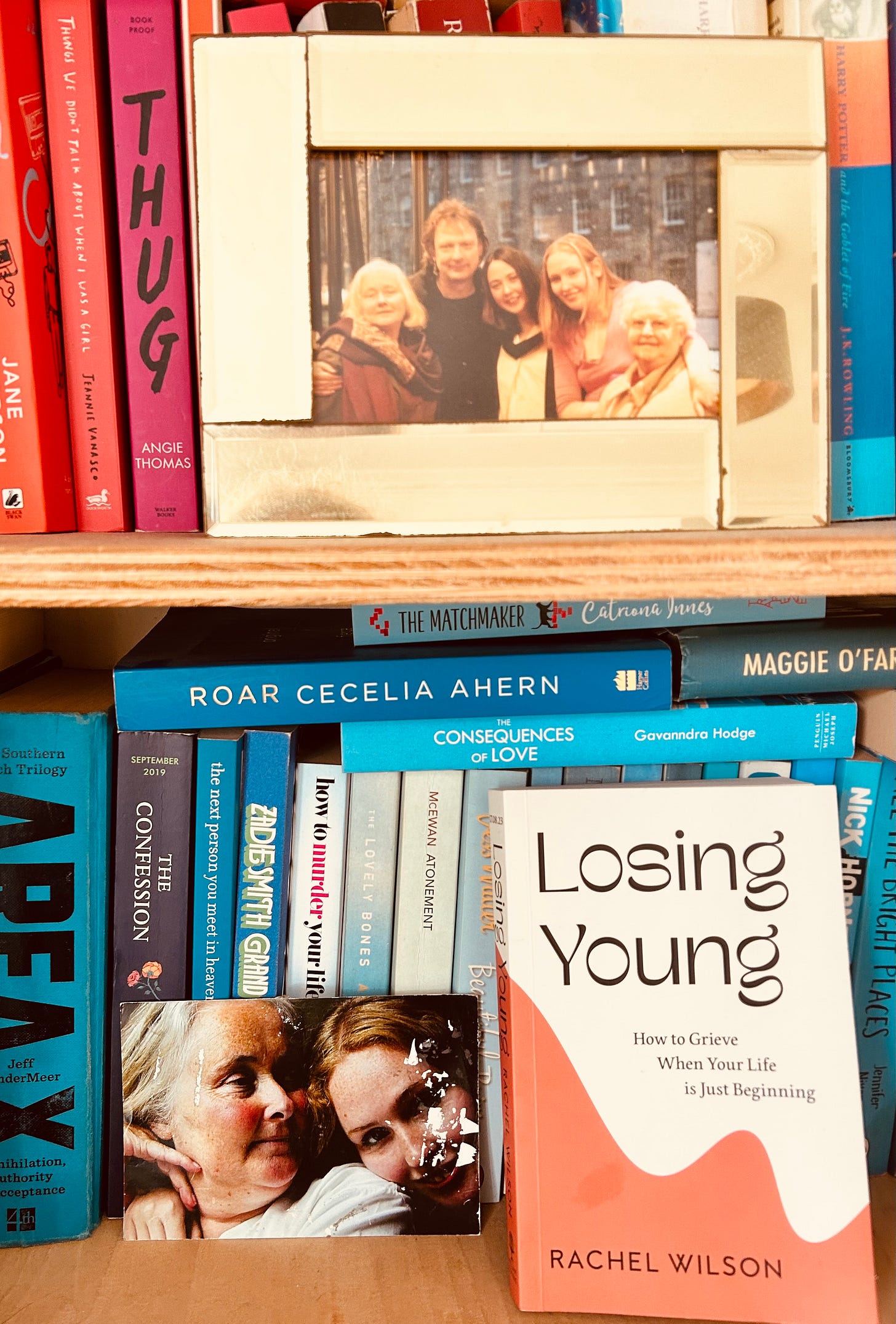

Rachel and her mum in Australia

As you discovered before setting up The Grief Network there's so little discussion or support for the unique complexities of losing someone in those quarter life years. For a long time I was like “everyone loses a parent.” I just kept thinking “I need to be more grown up in this” and even, years later, I was pitching a fiction book about a 19-year-old who loses her mum and the feedback I kept getting was “make the character younger, so it’s more shocking what happens to her” which only compounded this feeling I was doing grief wrong.

Writing through grief...

Crocuses in the snow is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. It’s kinder to think of it as sitting in a drawer. A thick wedge of paper, dust gathering between the sheets. Perhaps it’s in an antique desk, with clattering steel handles, waiting to be discovered - long after I…

What your network does, and the book does, make so much sense, as I was reading it and thinking this is so very, very unfair and awful… but it really isn’t discussed. Why do you think that is?

I ask this question right, right at the end of the book, when I look into the cultural side of grief. I felt very angry, as I, instinctively, thought that I was quite young to be losing a parent. I knew I wasn't a child, but I was also not prepared. I was nowhere near a [mature] life stage. I did think ‘I have to be more grown up, become my own caregiver’ but I did not have the support I needed.

Historically, grief support itself is quite a new phenomenon. It dates back to the 50s, when Cruse Bereavement started, and that was [originally] just for widows. We’ve only had specific child grief support since the 90s. Then couple that with us only really beginning to talk about our mid-twenties being a life stage that carries it’s own difficulties and characteristics [which began] in 2000 with the big ‘emerging adulthood’ study [where psychologists proposed that, with a focus of the ages of between 18-25, emerging adulthood is a distinct period of time, with its own sets of development that are different from adolescence.]

We also have people in the media saying we're all snowflakes. Most of the comments I have had have been from people who get it and people who understand or sympathise even if they haven't been through it themselves. But I do get the odd comment that's like “26 is not a young age. Stop crying!” Although sometimes I get the sense that people who comment are people who've lost someone [at a younger age]. And then I think fair enough.

But in general, I think culturally there’s this idea that we should be hesitant to really indulge 20-somethings. There’s a lack of understanding that what people are going through in their early 20s or late teens is as formative as being a teenager. As I've got older, everyone I know has something… it might not be a bereavement, but everyone has something that happens when they're young.

But it isn’t acknowledged, our stereotypes are silly students getting hammered all the time, like “just whiny Gen Z.” People don't think actually, if that had happened to me, how lost would I have been without that person?

The audience at one of The Grief Network’s events

Because, like you say you're in this weird period of flux and change. And I really appreciated how you say that, as a result of losing someone at this age, you can either feel mature beyond your years or almost stuck at the age you were at the time of the loss. I definitely feel the latter, like I’m only just growing up and learning from the moment now as I was so shaken by this huge thing… but I didn’t even acknowledge at the time it was so huge. I just tried to muddle on, ignoring it.

As a young person there’s even the difference say between being 19 and being 25. I remember being in my late teens and feeling a bit like I had everything sorted.

You’re arrogant with youth.

Yeah, you’re like “I can deal with this, I'm fine, blah, blah.” You really don't realise how young you are, [until you get older] I was able to [at 25] think this is actually pretty young, this is probably going to have an impact and I'm not sure what that will look like, which is why I wanted to meet other people [and set up the network]. It's very, very common that people feel that split sense of being like, “I’m just a young girl” but also feeling like “I have to be really independent, I can’t rely on anyone.” I think that's the one of the really distinct features of emerging adulthood. It’s literally living the Britney Spears song “I’m not a girl, not yet a woman.” You have parts of you that are striving towards independence, but the other part is like “I’m a kid, I don’t know what to do.” I think [facing a loss] really amplifies that split and means you’re stuck in that feeling a lot longer than other people who have more time and space to amble towards feeling like they’re a proper adult.

That’s the end of part one of my conversation with Rachel, in the next newsletter we’re discussing how television gets grief wrong and the role alcohol plays in a young person’s grieving process. As always, let me know what you think, and if you could share this post with someone who you think it would help, please do!

Losing Young by Rachel Wilson is out on the 17th August and is published by William Collins. It helped me so much and I hope it will help you too! Find more details of the book here, and for The Grief Network events you can find them, and Rachel, on Instagram here, and details of their events here. Interviewing Rachel made me realise how little I’ve spoken to people who have gone through what I have, so I’m definitely going to head along to one of their events soon.