Can we use our grief to heal others?

Part one of my conversation with The Rev Dr Marion Chatterley whose childhood grief spurred her into a lifetime of end-of-life care and bereavement counselling…

I called it my parachute dress. It was made of crinkly material and – if I have remembered correctly – was orchid purple. Its very existence made me look forward to Sundays. It was a special treat, from my grandma. A thank-you for going to church.

That was when I was five. I haven’t been in church much since. I have also (and I’m aware this is deeply unfair of me) made a judgement that I don’t have much in common with those who do go regularly. Ironically, I feel they’d judge me. I guess, in some ways, I’ve always viewed church people as ‘good’ (albeit slightly judgemental with it) and have tainted my own desires, and foibles as ‘bad.’ (They wouldn’t go to church simply so they could wear a flouncy outfit and show-off...)

This is a silly way of thinking, I’m more than aware of that. It’s also, most certainly, born from those parachute-dress days, as I sat, rustling in the back of my grandma’s super strict church hall. It’s even sillier when you consider that my dad (who definitely doesn’t judge me, or think of me as ‘bad’) attends a LGBTQ+ friendly church each week (my dad is the wonderful transgender playwright Jo Clifford, you can read her substack here.) It was there that she met Rev Marion Chatterley, who she recommended I speak to for this newsletter. And I’m so grateful that she did, as Marion’s words – and life lessons – have remained with me ever since.

I didn’t know what to expect from our conversation. Truthfully when I showed up at Marion’s door, my faux leopard print coat heavy and sodden with Edinburgh rain, I hadn’t done any preparation, or come with set questions. This is unusual for me. In my journalism I over-prepare: I’ve had five-minute slots with celebrities before where I’ve brought six A4 sheets of questions. But this newsletter is different – I have no angle, an editor hasn’t instructed me on the ‘line’ I simply must eek out of my interview subject… I only want to get know people – and how their grief has impacted them.

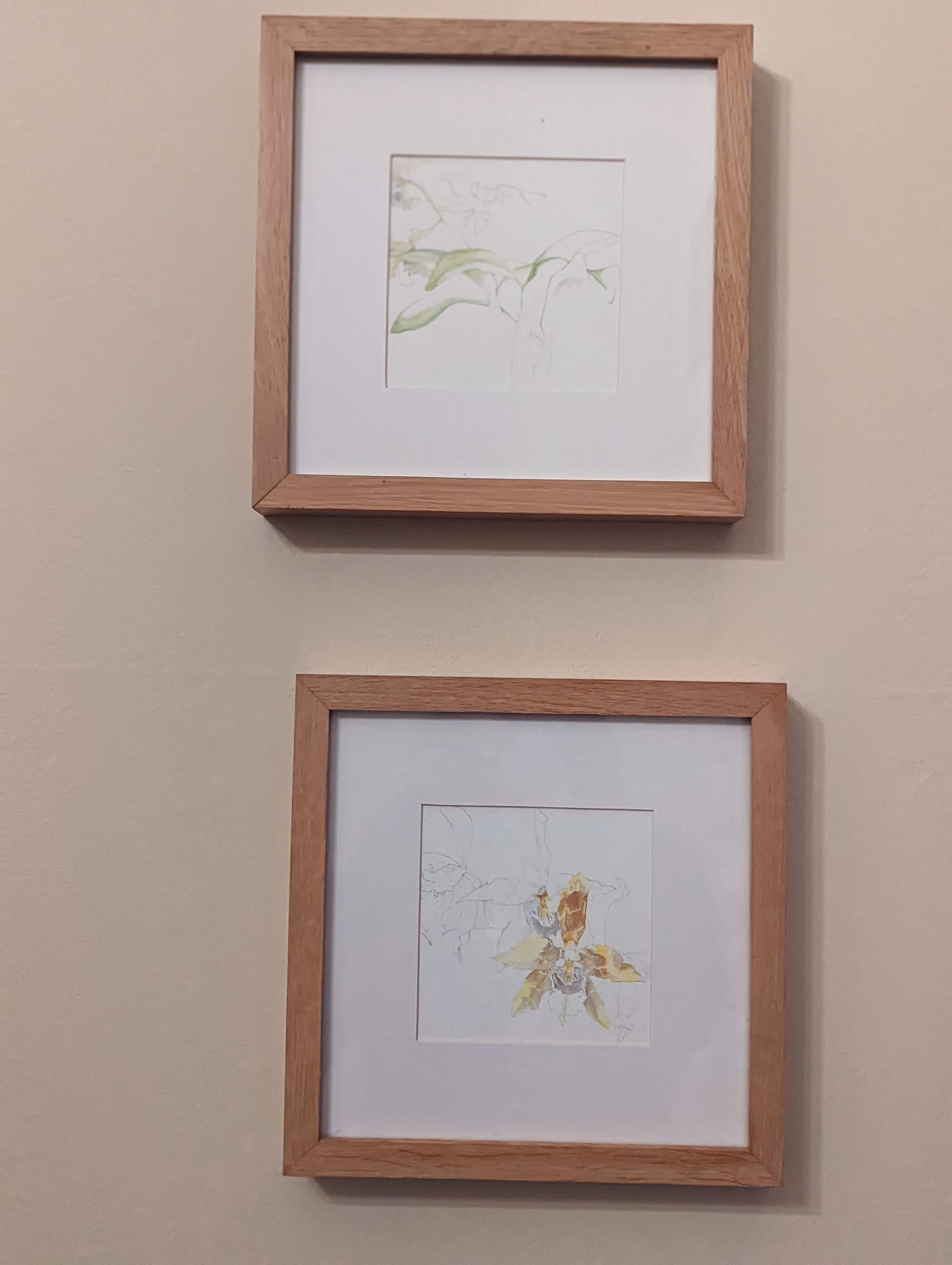

I’m also interested in speaking to those who have been close to death, professionally, to see how that influences their view of their own mortality. Marion has experience on both sides. Her childhood was, in her own words, “dominated by death.” And before she was ordained (she’s currently Vice Provost at St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh) she worked as a bereavement counsellor and was a chaplain in Milestone, the UK’s first HIV hospice. She also, to my delight, knew my mum when she was younger and proudly shows me two watercolour lilies my mum painted, which hang in her hallway.

After I left Marion’s flat, with almost floor-to-ceiling length windows overlooking the cathedral, I felt changed somehow. As mentioned, there are parts of myself that I am ashamed of. That I view as ‘bad’ qualities. One of these is my draw towards darkness, and the sulking characters within its shadows. It’s a pull that scares me. It can feel rotten and self destructive. Something I need to cleanse myself of.

But, as I learned, Marion shares this quality. She doesn’t think of it as ‘bad’ but, instead, recognises that her own grief, and past, has gifted her an ability to listen and empathise with people from all walks of life. She helps and heals people and, during our hour-long conversation, she helped and healed a part of me. I left feeling as though I understood myself more. As if I knew what path to pursue next.

I feel happy to be able to share our time together with you. Here’s part one…

Can you tell me about your early years?

My childhood was dominated by death. When I was born my sister was in hospital, under their care. She had a long term chronic condition and she died when she was 18. I was 13-years-old. Then my mother – who had been diagnosed with leukaemia when I was six – died three years later. So I had ten years of childhood completely dominated by [my mother’s] health and the fear that she was going to die.

It was a very troubled household. There was so much blame [my parents] saying things to me like “if you're cheeky to your mother you'll make her sick and she’ll go back to hospital.” That sort of narrative…. I’m not particularly wanting to blame [my parents], I don’t think it was a healthy environment but I don’t think they knew what to do.

This is something I have explored in the past and want to look into more. How when we’re in grief and we’re going through something so deep and painful, do we have control over our own behaviour?

I think that’s absolutely right. There are decisions [my parents made] and I don’t think they considered the impact they would have on me.

I wasn’t allowed to go to my sister’s funeral and - it’s funny how you get these really strong, sharp, memories – I can remember cycling to school knowing that my parents had just set off for my sister’s funeral. It was just “there’s no need for you to go.” She’d been quite disappeared from the family and, I think, probably by the time she had died my mum had stopped visiting her. My father went every single week and would bring her a bottle of Lucozade, one of the ones in the glass bottle with the crinkly wrapper. I suspect [by the time she died] in [my mother’s] mind she was a sort of non-person.

As during your sister’s last years, your mum was also facing leukemia. What can you remember about that time?

When my mother died, we had visited her in the hospital and it was clear she was more unwell. But then when we went in to see her [a few days later] and she was feeling a bit better and she’d put her lippy on. I can remember my dad saying “you had us really worried there!” She died the next day.

What impact do you think all of this has had on your life, and your chosen path?

It’s been huge. At first I went through a really crazy time. As we just didn’t talk about the deaths of my mum and sister. My father, looking back, wasn’t coping. But he was of that generation where he would never admit that.

I drank a lot and took drugs and it was chaotic. Eventually I found my way into counseling and therapy, and after that I trained as a counselor myself. I knew I wanted to do bereavement counseling with children. I worked for Cruse for about fifteen years and I only stopped when I was ordained.

What age were the children you were seeing?

Primary school. We would often get them to draw things so we could use that as a way to get them to tell us how they were feeling. It was about creating a space where they could talk freely. Because if you've got a child where one parent has died, particularly in primary school children, they’re very protective of the other parent. They say things like “I can’t talk about my dad because it makes my mummy cry.” But clearly they need the space where they can do that.

That’s so true. And, at any age, it can be so hard to be able to grieve with your family as you’re also protective of the ones you love. When we lost mum we, of course, wanted to talk about her. But every time we did one of us would cry, then it would set everyone else off and – at the time – I couldn’t bear it. Even though I know that crying is a healthy outlet, it was the sensation of it. So, I stopped talking about her in a way that, looking back, wasn’t healthy. I couldn’t face the tears.

I think there’s something about that sort of really deep, traumatizing crying that you don’t want to do as it’s physically painful.

Did working with these children help you re-evaluate parts of your own childhood? Did it help you process at all?

It made me incredibly sad that there was nothing [like that on offer when I was younger.] I can remember coming back to school and the teachers saying to me “I heard about your mother, I read the notice on the staff board.” I still think “how dare you?” It meant I almost became an exhibit. You think everyone’s looking at you and thinking ‘she doesn’t have a mum anymore.’

But I think working with children and young people helped [process these memories]. I also ran a group for single, bereaved parents with primary school aged children. That was quite therapeutic, you just hear stories in a different way. There’s also something quite encouraging about realising that not everybody is stuck in the 1970s.

I can see that. As, even when you were talking about your dad I was thinking of a lot of men that I know who are bad at talking about their emotions. It can make you think ‘oh my god nothing has changed’ but actually so much has. You can’t get stuck thinking it hasn’t.

I think probably the most healing thing for me has been the relationship I have had with my own children. And being able to have a different kind of relationship [from how I was raised.] But, the thing that still surprises me how something – seemingly from no where – can tap into your grief.

Certainly when I had children and I didn’t have my mum and everyone else around me was saying “I didn’t know what to do so I phoned my mum.” I also had that classic thing of when I became the age my mum was when she died. She was in her forties when she died and I cannot tell you how happy I was to turn 50.

A lot of people I know view religion and churches as very judgemental. But that’s the opposite of what you offer, as you work with people from all walks of life and are there to listen, and offer non-judgemental support…

I have worked with a lot of people who have been really damaged by faith communities. Faith communities have treated LGBT people historically appallingly, and in some places that remains. Similarly if you’re a drug user it’s quite hard to find yourself welcomed into a church.

I think there but for the Grace of God. It could have been me who ended up with a needle in my arm. Particularly, when you're struggling with grief and there was a time of my life when I was a bit of a mess.

When I look back on my twenties I can see that I was definitely drinking as a form of extreme self-medication. I wrote my dissertation on heroin addiction and, as part of that, I interviewed a man who had been a recreational heroin user. He’d managed to have control over the drug for a few years… but then something awful happened to him. He said – and it’s always stayed with me – “I had the thing that would take the pain away.” Of course, it’s not the thing that going to take away the pain long-term, it will only add more. But short-term it is…

I think when you're that raw… We’re looking for something different and, for many of us, that can involve really unhealthy coping strategies.

I also think that, looking back, I desperately needed to be loved. And to be unconditionally loved. My mother was ill for a really long time but also she wasn’t a particularly good mother.

So you didn't have that unconditional love?

When you're a child you always imagine it will change and that you'll get what you need. I think that I thought – up until the point she died – that there was going to be this transformation and she would turn into this loving parent. I was waiting and waiting and longing for that. Then once she died that possibility was gone. I can see now, with my rational head, that clearly that was never going to happen.

Do you think that helped you? That her dying meant you could face up to the reality? As you were no longer longing for something that would never come?

I think so. In a funny sort of way, there was almost a freedom [in her death]. But the revelation of that came a lot later.

What do you think eventually led you to realise that these coping strategies weren’t good for you? And helped you move on to a new way of living?

It was exploring the spiritual side. It wasn’t Christianity at first. I got really into meditation and that made a difference. I was finding something inside myself that I could value.

You’re such a nurturing person, and I find it so interesting that you grew up in a household where you weren’t nurtured…

There’s this idea of the Wounded Healer [the idea that those who are compelled to help people who are damaged, because they themselves are damaged]. There’s absolute truth in it. I do think that I find it easier to get alongside people who are really troubled. I know our stories can be completely different but I do know what it’s like to be really broken. Another important part in discovering new coping strategies was, for me, learning I was good at listening to people. I found a focus in that, a hope.

Next week on the newsletter (said in movie trailer voice) my conversation with Marion discusses what makes a good listener, how to help people during their toughest moments and what she’s learned about life from those who are dying.

I’d love to hear from you as well, on whether you think your grief has helped you help others. And, as always, if you can’t become a paid subscriber the best way to support my work is to share it with others. Thank you!